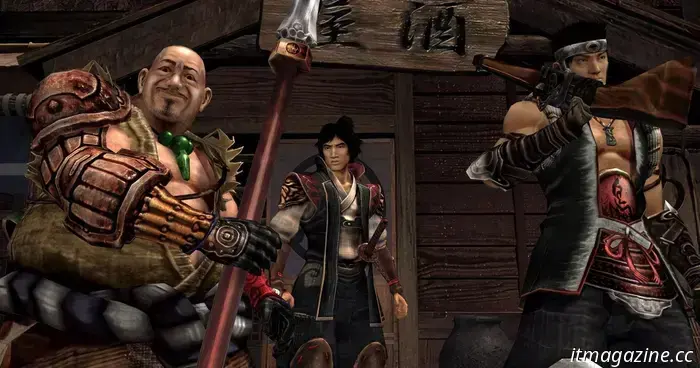

The remaster of Onimusha 2: Samurai’s Destiny shows that games of this caliber are no longer made.

“They don’t make them like they used to.”

As a film enthusiast, no expression in English elicits more eye-rolling from me than this one. For years, I have heard this phrase recited to lament the state of cinema. I find it to be a rather foolish remark. For one, it’s obvious that they don’t. The world of art, along with the tools we use to create it, evolves. What bothers me more is when this phrase is employed to disparage contemporary films. The suggestion that the art we grew up with is inherently superior to what exists today often comes across as a stubborn refusal to embrace change.

However, after playing — quite unexpectedly — Capcom’s new remaster of Onimusha 2: Samurai’s Destiny, I find myself reflecting on that phrase. Revisiting the PS2 classic in 2025 feels like uncovering an ancient artifact. It serves as a mesmerizing time capsule, distinct from any new release I’ve experienced this year. Its cinematic aspirations, combined with the limitations of video games from that period, produce an unmistakable quality that is hard to replicate. In this instance, they genuinely don’t make them like they used to.

Back to 2002

Before engaging with the remaster, my relationship with Onimusha has always been somewhat distant. Growing up without a PlayStation 2, I was nonetheless a devoted reader of magazines like EGM, keeping up with every significant game on the system. From that vantage point, Onimusha appeared larger than life, possessing the essence of a high-profile game akin to titles like Shadow of the Colossus. Magazine screenshots led me to envision a dark, serious action game reminiscent of how Elden Ring seems to me today.

However, I had to recalibrate my expectations right from the start of Onimusha 2: Samurai’s Destiny. The opening narrative quickly informs me that Nobunaga Oda is a.) deceased and b.) leading an army of demons. This is delivered with such seriousness in the voiceover that I couldn’t help but laugh. It’s completely absurd, a B-movie setup presented with the gravitas of a historical epic.

This tone persisted throughout my gameplay. Capcom aimed high in 2002, striving to create a genuinely cinematic experience nearly a decade before technology caught up. If this were a film, it might be described as “amateur.” The script is filled with corny jokes, as characters consistently exclaim “hubba hubba!” about women. Cutscenes are marked by awkward camera angles that never quite seem appropriate. The voice acting carries the essence of high school theater.

But make no mistake: It’s utterly fantastic.

Capcom

Like many games of its time, Onimusha 2 feels surreal. It’s quirky enough in every aspect that it borders on the bizarre. A fierce demon might suddenly appear, deliver an exaggerated monologue, then dash in and out of bushes like a character from a Scooby Doo episode. On paper, it’s comical, yet there’s a genuine respect for the lore and universe that Capcom has crafted. The tone oscillates between playful and serious—two sentiments that many modern games typically keep separate. This tonal blend isn’t unique to Onimusha; it reflects a broader trend of that era. I experience similar feelings when playing Capcom’s early Resident Evil titles, which are packed with stilted performances and awkward lines, yet I can dive into their world with ease.

This concept extends beyond cutscenes into the gameplay as well. It’s evident that Onimusha emerged following Resident Evil’s success. It utilizes fixed camera angles that build tension by concealing threats around every corner. Rooms are filled with random puzzle boxes that I need to figure out to reveal hidden pathways. I discover the world through straightforward item descriptions that appear flatly on screen. All these design elements of the time create a distinct quality that is both specific and difficult to articulate. It’s an incredibly atmospheric experience—claustrophobic and eerie, even in its silliest moments. I’m not merely escaping into a world where I have full control; I’ve fallen into a mysterious realm governed by a creator’s rules, and I must understand how to navigate it to survive. It’s akin to wandering a hedge maze on a foggy evening.

Modern video games don’t evoke this feeling anymore—at least not the major ones. Developers have finally figured out how to create a “cinematic” feel, raising the standards for acting, writing, and cinematography. This has led to digital worlds that appear more familiar, grounded in a visual language that feels recognizable. Even this year’s Dynasty Warriors: Origins replaces the series’ quirky acting and puzzling eccentricities with something much more subdued. Playing Onimusha 2 feels like watching a Hollywood drama from the 1930s, which showcases stage acting and grand gestures.

That’s likely why I’m so enthusiastic

Other articles

Fortnite has made its return to Apple’s App Store… in a way.

Epica Games' Fortnite has finally returned to Apple's App Store after a five-year hiatus, but the situation isn't entirely simple.

Fortnite has made its return to Apple’s App Store… in a way.

Epica Games' Fortnite has finally returned to Apple's App Store after a five-year hiatus, but the situation isn't entirely simple.

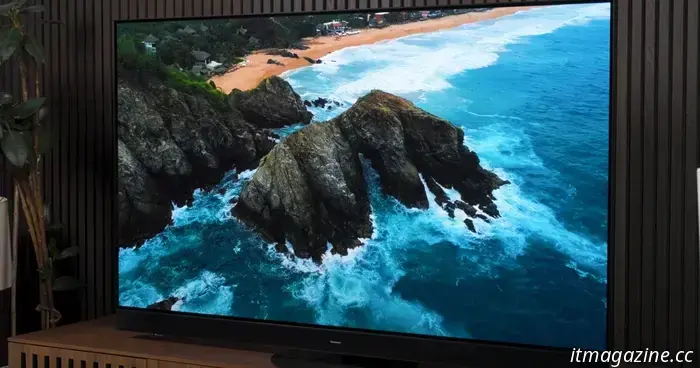

Get a $300 discount when you purchase the 86-inch LG QNED80 today.

The LG 86-inch QNED80 is discounted this week to $1,000, reflecting a $300 reduction from its regular price of $1,300.

Get a $300 discount when you purchase the 86-inch LG QNED80 today.

The LG 86-inch QNED80 is discounted this week to $1,000, reflecting a $300 reduction from its regular price of $1,300.

Google's latest Flow tool introduces AI capabilities to video production.

Google I/O 2025 This article is part of our comprehensive coverage of Google I/O Updated less than 8 hours ago Google's most recent I/O event, held on Tuesday, highlighted a remarkable growth of AI throughout its expanding lineup of products, introducing new generative tools such as Imagen 4 for images, Veo 3 for video, and Flow […]

Google's latest Flow tool introduces AI capabilities to video production.

Google I/O 2025 This article is part of our comprehensive coverage of Google I/O Updated less than 8 hours ago Google's most recent I/O event, held on Tuesday, highlighted a remarkable growth of AI throughout its expanding lineup of products, introducing new generative tools such as Imagen 4 for images, Veo 3 for video, and Flow […]

Summary of Google IO 2025: 5 major announcements you should be aware of.

Google covered a great deal during its IO keynote, but here are the main points you should be aware of.

Summary of Google IO 2025: 5 major announcements you should be aware of.

Google covered a great deal during its IO keynote, but here are the main points you should be aware of.

Memorial Day TV sales 2025: Savings on Samsung, Sony, LG, and others.

Memorial Day TV sales are currently underway, offering discounts on televisions from well-known brands such as Samsung, Sony, and LG.

Memorial Day TV sales 2025: Savings on Samsung, Sony, LG, and others.

Memorial Day TV sales are currently underway, offering discounts on televisions from well-known brands such as Samsung, Sony, and LG.

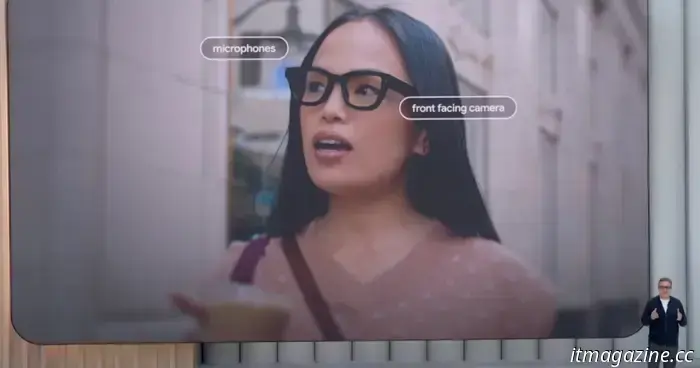

Google is aiming to acquire your upcoming pair of high-end sunglasses.

During Google I/O 2025, Google clearly expressed its desire to take the lead in the luxury smart eyewear market. Here's the significance of that for you.

Google is aiming to acquire your upcoming pair of high-end sunglasses.

During Google I/O 2025, Google clearly expressed its desire to take the lead in the luxury smart eyewear market. Here's the significance of that for you.

The remaster of Onimusha 2: Samurai’s Destiny shows that games of this caliber are no longer made.

Capcom's latest remaster of Onimusha 2: Samurai's Destiny serves as a time capsule reflecting the diverse golden age of the PS2.