A quarter of a century following its debut, The Virgin Suicides continues to embody profound humanity.

“In the end, we had pieces of the puzzle,” states Giovanni Ribisi, serving as the unseen narrator in Sofia Coppola’s debut film, The Virgin Suicides, which was released twenty-five years ago today. “But regardless of how we arranged them, gaps remained.” How can we convey the stories of those we do not fully understand but believe are deserving of being told?

By examining the idea of an all-knowing third-person narrative and drawing from the stunning achievement of the 1993 Jeffrey Eugenides novel it's based on, Coppola's film continues to be as rich and captivating today as it was when it first premiered a quarter of a century ago.

Ribisi acts as the collective voice of a diverse group of neighborhood boys from a Detroit suburb in the 1970s who are both infatuated with and intrigued by the Lisbon sisters, four ethereal blondes aged 13 to 17, each of whom meets a tragic end. We cannot identify which boy he is; they move in a close-knit group, sharing their teenage desires in hushed tones while he consistently refers to “we” in his narrative. This makes the audience part of the story, engaging with it. We watch along with these teenagers and, like them, feel powerless. We too hold only fragments of the puzzle.

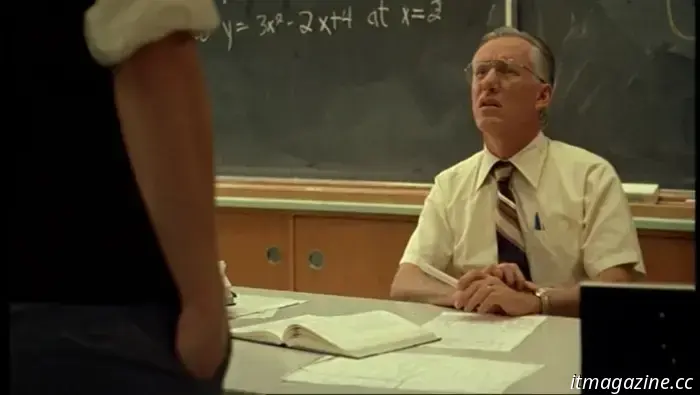

The Lisbon sisters include Lux (Kirsten Dunst), Cecilia (Hanna R. Hall), Mary (A.J. Cook), Therese (Leslie Hayman), and Bonnie (Chelse Swain). Dunst, who appeared in three films within a year—Dick, Drop Dead Gorgeous, and this one—leaves the most lasting impact. She gazes at the camera through an inscrutable haze; she is both accessible and beyond reach. Coppola fell for her and has made her a muse in various films, from the whimsical (Marie Antoinette) to the stark (The Beguiled). Observing the start of their artistic relationship on screen is captivating; both artists bring beauty to each other. (Ribisi also became a frequent collaborator, marking the beginnings of the Coppola legacy.)

The underlying theme of The Virgin Suicides is not merely the dreamy unreality of teenage delirium, as often claimed. Instead, it contrasts the harshness of reality with that unreality—the idealized girl, appearing almost divine from afar, ultimately found hanging in a basement.

Eugenides’ poignant prose contributes significantly here. In adapting the screenplay, Coppola wisely allowed it the space to deeply resonate within the audience’s awareness, similar to its effect on the page. Her direction, in any case, matches his achievement and makes this debut feel, even now, like an exhilarating indication of future talents.

This film stands out as a period piece devoid of sentimentality. Its immediacy is so striking that the conclusion almost shocks. Part of its charm is how it sincerely reminisces about an analog era we’ve lost. The neighborhood boys, responding to the harsh restrictions imposed on the Lisbon sisters by their strict parents (James Woods and Kathleen Turner), reach out via phone and play a record over the line: Hello It’s Me by Todd Rundgren.

In the book, they play Make It with You by Bread—a more straightforward choice, perhaps too costly for the film’s music budget, which had already included selections from Heart, Al Green, Gilbert O’Sullivan, Electric Light Orchestra, 10cc, and Styx. Released at the start of the digital era, The Virgin Suicides exhibited nostalgia for a time when such gestures were possible, allowing the audience to feel that nostalgia genuinely and profoundly.

Every era has its recalled decade. The 1970s looked back to the '50s, considered a period of innocence and prosperity. It was no coincidence that shows like Happy Days, Grease, and American Graffiti debuted in the bleak post-Watergate era of the '70s. In the '90s, while most were enjoying great comfort and wealth, they looked back to the '70s—a time when young people encountered risk and experienced sexuality in a way that was rapidly disappearing. I find parallels between The Virgin Suicides and the outstanding 1997 film The Ice Storm, adapted from a novel by Rick Moody.

Moody, like Eugenides, graduated from Brown University (attending concurrently in the post-pop fiction wave inspired by David Foster Wallace) and, like Eugenides, wrote his debut novel about teenagers facing deadly violence in seemingly safe middle-class suburban settings of the '70s. Other classics from the '90s and early 2000s that explore the ’70s—Almost Famous, Dazed and Confused, and Goodfellas—follow similar harrowing coming-of-age narratives.

As with all Coppola projects, this too is a family affair; Sofia’s brother Roman (a frequent Wes Anderson collaborator) serves as the second-unit director, her cousin Robert Schwartzman (brother of Jason) plays

Other articles

NYT Strands today: clues, spangram, and solutions for Monday, April 21.

Strands offers a challenging twist on the traditional word search from NYT Games. If you're having difficulty and can't figure out today's puzzle, we've got assistance and clues for you right here.

NYT Strands today: clues, spangram, and solutions for Monday, April 21.

Strands offers a challenging twist on the traditional word search from NYT Games. If you're having difficulty and can't figure out today's puzzle, we've got assistance and clues for you right here.

How to buy Reboot Cards in Fortnite

Have you ever forgotten to pick up a teammate's Reboot Card in Fortnite? You can now buy them in the game, and here's how you can do it.

How to buy Reboot Cards in Fortnite

Have you ever forgotten to pick up a teammate's Reboot Card in Fortnite? You can now buy them in the game, and here's how you can do it.

Answers for the NYT Mini Crossword for Monday, April 21.

The NYT Mini crossword may be significantly smaller than a standard crossword, but it's still quite challenging. If you're having trouble with today's puzzle, we have the solutions for you.

Answers for the NYT Mini Crossword for Monday, April 21.

The NYT Mini crossword may be significantly smaller than a standard crossword, but it's still quite challenging. If you're having trouble with today's puzzle, we have the solutions for you.

Trump’s ‘war on science’ presents a significant opportunity for Europe to attract major tech talent.

The Trump administration's "war on science" has raised concerns about a potential brain drain from the US, which may advantage European technology.

Trump’s ‘war on science’ presents a significant opportunity for Europe to attract major tech talent.

The Trump administration's "war on science" has raised concerns about a potential brain drain from the US, which may advantage European technology.

The five most promising scaleups in France are joining TECH5's 'Champions League of Tech.'

Five French scaleups have been selected for TECH5, known as the "Champions League of Tech." They will now vie for the title of the leading scaleup in Europe.

The five most promising scaleups in France are joining TECH5's 'Champions League of Tech.'

Five French scaleups have been selected for TECH5, known as the "Champions League of Tech." They will now vie for the title of the leading scaleup in Europe.

The Hundred Line: Last Defense Academy review: the pupil exceeds the mentor

The Hundred Line: Last Defense Academy enhances the Danganronpa concept, delivering a new and invigorating tactics RPG experience.

The Hundred Line: Last Defense Academy review: the pupil exceeds the mentor

The Hundred Line: Last Defense Academy enhances the Danganronpa concept, delivering a new and invigorating tactics RPG experience.

A quarter of a century following its debut, The Virgin Suicides continues to embody profound humanity.

Since its premiere on April 21, 2000, The Virgin Suicides has proven to be a noteworthy debut feature by Sofia Coppola that has endured over time.