European cloud providers present an alternative to AWS, Azure, and GCP.

When the modern internet started to take shape in the early 2000s, it was challenging to find hosting services and resources for the emerging dynamic web applications. A database was essential for storing application data, but these were often slow, costly, and prone to failure, which could halt applications if a single instance went down. Similarly, servers required for running interpreted languages like PHP, Python, or Ruby were also expensive, required configuration, faced security issues, and frequently encountered resource shortages that again led to application downtime.

For anyone with a limited budget, operating web 2.0-era applications demanded continuous adjustments, performance optimization, and cost management, all within the strict limits set by service providers on what users could modify and manage.

Over the years, a diverse range of hosting providers has emerged to tackle the growing complexity and demands of web applications. In the last decade, a significant shift has occurred with many applications migrating to a new model called “cloud hosting.” The term “cloud” can be ambiguous, summarized by the saying, “The cloud is just someone else’s computer.” This model simplifies and abstracts the complexities of infrastructure management. Instead of focusing on servers, users can concentrate on services and instances of those services.

Today, if a database is underperforming, adding another instance is the solution. And if the number of database and application instances becomes overwhelming, additional services can be incorporated to manage them.

Recently, the concept of “serverless” has gained immense popularity, striving to reduce server interactions down to simple function calls. While a server still manages the function calls and responses internally, the premise is that developers should not need to concern themselves with server management and should focus solely on data exchange.

More than two decades later, one might presume that web application developers have it easier now, but that's not quite the case. Numerous challenges persist in developing and maintaining applications in the cloud, though several European operators are actively working to alleviate these difficulties.

Before delving into their contributions, here’s a brief glossary of terms:

- Private cloud: Services allocated to a single customer.

- Public cloud: Services utilized by multiple customers.

In both scenarios, client data remains confidential, and services may operate across one or several locations. The key distinction lies in the provider assigning a specific digital space exclusively to that customer, potentially defined by software or hardware configurations, which could involve a dedicated server operating remotely or on-premises.

Now, let's explore the issues present in the cloud computing landscape.

The cloud landscape is consolidated and monopolized

Although there are numerous cloud computing providers, most people tend to think of just three: Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Platform (GCP)—referred to as the “hyperscalers” of hosting.

The web hosts a vast array of publicly and privately available sites, making exact figures difficult to ascertain. However, data from builtwith.com indicates that approximately 12% of all websites—around 86.8 million—operate on AWS, with the other two hosting an additional 12% combined. Among hosting companies that label themselves as “cloud,” according to techjury.net, these figures rise to 32% for AWS, 23% for Azure, and 10% for GCP.

However, the complexities arise from defining what constitutes a website, as hyperscalers provide a multitude of services that developers utilize for various application components, some of which are critical; their unavailability can disrupt entire applications.

This consolidation has led to significant service outages affecting various online services. Consequently, many developers have adopted a multi-cloud or hybrid-cloud strategy to spread risk across different providers. While this mitigates technical risks, it also boosts revenue for all cloud providers while adding complexity.

This consolidation centralizes power within a few companies. If any of them alter their policies, countless businesses could find themselves without operational solutions. It is also concerning that the top three—and indeed, the top five—are US companies, with the exception of China’s Alibaba.

The US has established data privacy, security, and law enforcement protocols that worry numerous enterprises and jurisdictions. Although these companies offer global hosting options across various legal frameworks, a shift in US politics could threaten these digital boundaries. No matter how improbable some scenarios may appear, consolidation poses inherent risks.

Diversifying the cloud

Developers and their organizations are not inclined to abandon the cloud entirely. Instead, they are seeking alternatives from hyperscale hosts, particularly in Europe, where increasing regulations and uncertainties surrounding American services, compounded by a nationalistic push for using European solutions, create new global opportunities for both established and emerging hosting providers.

I spoke with three major hosting providers in Europe to gauge their perspectives on these trends and their vision for the future of web hosting over the next 20 years. Two of them—France’s OVH, which hosts about 4% of websites, and Germany’s Hetzner, which manages around 5.5%—have been operational since the late 199

Other articles

The teaser trailer for The Life of Chuck offers a glimpse into the emotional adaptation of Stephen King's work.

Neon has unveiled the teaser trailer for The Life of Chuck, an adaptation of a Stephen King short story by Mike Flanagan.

The teaser trailer for The Life of Chuck offers a glimpse into the emotional adaptation of Stephen King's work.

Neon has unveiled the teaser trailer for The Life of Chuck, an adaptation of a Stephen King short story by Mike Flanagan.

The James Webb Space Telescope captures a breathtaking image of the enchanting Flame Nebula.

The James Webb Space Telescope has taken a picture of the Flame Nebula as part of its study on failed stars known as brown dwarfs.

The James Webb Space Telescope captures a breathtaking image of the enchanting Flame Nebula.

The James Webb Space Telescope has taken a picture of the Flame Nebula as part of its study on failed stars known as brown dwarfs.

The new mode in Rainbow Six Siege X is ideal for beginners such as myself.

Rainbow Six Siege X will enhance Ubisoft's popular live service game by introducing an all-new mode designed specifically for beginners.

The new mode in Rainbow Six Siege X is ideal for beginners such as myself.

Rainbow Six Siege X will enhance Ubisoft's popular live service game by introducing an all-new mode designed specifically for beginners.

Step aside iPhone, here's a smartphone featuring a huge battery and an integrated projector.

The Tank 3 Pro by 8849 features a substantial battery, exceeds the RAM capacity of many gaming laptops, and has a battery life that lasts up to a week.

Step aside iPhone, here's a smartphone featuring a huge battery and an integrated projector.

The Tank 3 Pro by 8849 features a substantial battery, exceeds the RAM capacity of many gaming laptops, and has a battery life that lasts up to a week.

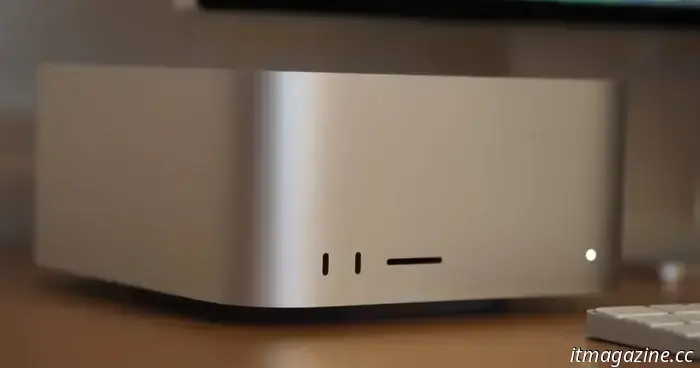

The $14,000 Mac Studio is extremely costly — but don't say it's overpriced.

Apple products can carry a hefty price tag, as demonstrated by the $14,000 Mac Studio. However, are they truly overpriced? You may be surprised to find that they can often represent a genuine value.

The $14,000 Mac Studio is extremely costly — but don't say it's overpriced.

Apple products can carry a hefty price tag, as demonstrated by the $14,000 Mac Studio. However, are they truly overpriced? You may be surprised to find that they can often represent a genuine value.

The Samsung S90D 42-inch OLED TV is now available with a $400 reduction in price.

The Samsung 42-inch S90D 4K OLED is available at a discounted price today. Don't miss out on this incredible premium TV, now priced at $1,000, but hurry!

The Samsung S90D 42-inch OLED TV is now available with a $400 reduction in price.

The Samsung 42-inch S90D 4K OLED is available at a discounted price today. Don't miss out on this incredible premium TV, now priced at $1,000, but hurry!

European cloud providers present an alternative to AWS, Azure, and GCP.

European cloud companies are offering an alternative to AWS, Azure, and GCP. Are the new challengers capable of competing with the hyperscalers?